| Sr. No. | Case Law & Citation | Relevant Extracts (The Principle) |

| 1. | Sunil Batra (I) v. Delhi Administration (1978) 4 SCC 494 (Constitution Bench - 5 Judges) | Para 211: "It is now well settled that the retributive theory has had its day and is no longer valid. Deterrence and reformation are the primary objectives of punishment... The prisoner does not cease to be a human being and he acts like a human being." Para 53: "Brutal man-handling... is not a valid penal programme... Retribution and deterrence are not the sole ends of punishment; reformation and rehabilitation are the primary objectives. The prison system must be therapeutic, not traumatic." Para 244: "Barbaric treatment of a prisoner from the point of view of his rehabilitation and acceptance and retention in the mainstream of social life, becomes counter-productive in the long run." |

| 2. | Maru Ram v. Union of India (1981) 1 SCC 107 (Constitution Bench - 5 Judges) | Para 43: "It is thus plain that crime is a pathological aberration, that the criminal can ordinarily be redeemed, that the State has to rehabilitate rather than avenge. The sub-culture that leads to anti-social behaviour has to be countered not by undue cruelty but by re-culturisation." Para 43: "The infliction of harsh and savage punishment is thus a relic of past and regressive times... We, therefore, consider a therapeutic, rather than an 'in terrorem' outlook, should prevail in our criminal courts, since brutal incarceration of the person merely produces laceration of his mind." Para 45: "It makes us blush to jettison Gandhiji and genuflect before Hammurabi, abandon reformatory humanity and become addicted to the 'eye for an eye' barbarity." Para 72(12): "In our view, penal humanitarianism and rehabilitative desideratum warrant liberal paroles... so that the dignity and worth of the human person are not desecrated by making mass jails anthropoid zoos." |

contact for clarification or assistance at talha (at) talha (dot) in

Search The Civil Litigator

Friday, December 12, 2025

retributive theory is not valid

Tuesday, August 5, 2025

Judicial Considerations in Bail Orders

(a) Ram Govind Upadhyay v. Sudarshan Singh, (2002) 3 SCC 598 (Para 4): Emphasises that the gravity of the offence alone cannot be the sole basis for denial of bail; the court must assess the risk of tampering with evidence or fleeing from justice.

(b) State of Maharashtra v. Dhanendra Shriram Bhurle, (2009) 11 SCC 541 (Para 7): Reinforces the need to balance individual liberty with societal interest. Courts must be cautious while exercising discretion.

(c) Reasoning to be given in Bail Orders by Courts (Paras 10–13): It is settled law that bail orders must record reasons – vague or mechanical orders fail the constitutional mandate of fairness.

(d) Kalyan Chandra Sarkar v. Rajesh Ranjan, (2004) 7 SCC 528 (Para 11): Reiterates that even at the stage of considering bail, courts must be satisfied that there is no prima facie case, and must record reasons for grant or denial.

(e) Ramesh Bhavan Rathod v. Vishanbhai Hirabhai Makwana, (2021) 6 SCC 230 (Paras 23–24): Criticises cryptic bail orders and insists on a rational application of judicial mind reflecting judicial discipline.

(f) Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy v. CBI, (2013) 7 SCC 439 (Para 35) (Bail): Recognises that economic offences, though not of violence, are grave and affect public trust; bail must be granted cautiously.

Wednesday, July 16, 2025

Tuesday, June 10, 2025

Expert opinion

Ramesh Chandra Agrawal v. Regency Hospital Ltd., (2009) 9 SCC 709

18. The importance of the provision has been explained in State of H.P. v. Jai Lal [(1999) 7 SCC 280 : 1999 SCC (Cri) 1184] . It is held, that, Section 45 of the Evidence Act which makes opinion of experts admissible lays down, that, when the court has to form an opinion upon a point of foreign law, or of science, or art, or as to identity of handwriting or finger impressions, the opinions upon that point of persons specially skilled in such foreign law, science or art, or in questions as to identity of handwriting, or finger impressions are relevant facts. Therefore, in order to bring the evidence of a witness as that of an expert it has to be shown that he has made a special study of the subject or acquired a special experience therein or in other words that he is skilled and has adequate knowledge of the subject.

19. It is not the province of the expert to act as Judge or Jury. It is stated in Titli v. Alfred Robert Jones [AIR 1934 All 273] that the real function of the expert is to put before the court all the materials, together with reasons which induce him to come to the conclusion, so that the court, although not an expert, may form its own judgment by its own observation of those materials.

20. An expert is not a witness of fact and his evidence is really of an advisory character. The duty of an expert witness is to furnish the Judge with the necessary scientific criteria for testing the accuracy of the conclusions so as to enable the Judge to form his independent judgment by the application of these criteria to the facts proved by the evidence of the case. The scientific opinion evidence, if intelligible, convincing and tested becomes a factor and often an important factor for consideration along with other evidence of the case. The credibility of such a witness depends on the reasons stated in support of his conclusions and the data and material furnished which form the basis of his conclusions. (See Malay Kumar Ganguly v. Dr. Sukumar Mukherjee [(2009) 9 SCC 221 : (2009) 10 Scale 675] , SCC p. 249, para 34.)

21. In State of Maharashtra v. Damu [(2000) 6 SCC 269 : 2000 SCC (Cri) 1088 : AIR 2000 SC 1691] , it has been laid down that without examining the expert as a witness in court, no reliance can be placed on an opinion alone. In this regard, it has been observed in State (Delhi Admn.) v. Pali Ram [(1979) 2 SCC 158 : 1979 SCC (Cri) 389 : AIR 1979 SC 14] that "no expert would claim today that he could be absolutely sure that his opinion was correct, expert depends to a great extent upon the materials put before him and the nature of question put to him".

22. In the article "Relevancy of Expert's Opinion" it has been opined that the value of expert opinion rests on the facts on which it is based and his competency for forming a reliable opinion. The evidentiary value of the opinion of an expert depends on the facts upon which it is based and also the validity of the process by which the conclusion is reached. Thus the idea that is proposed in its crux means that the importance of an opinion is decided on the basis of the credibility of the expert and the relevant facts supporting the opinion so that its accuracy can be crosschecked. Therefore, the emphasis has been on the data on the basis of which opinion is formed. The same is clear from the following inference:

"Mere assertion without mentioning the data or basis is not evidence, even if it comes from an expert. Where the experts give no real data in support of their opinion, the evidence even though admissible, may be excluded from consideration as affording no assistance in arriving at the correct value."

23. Though we have adverted to the nature of disease and the relevancy of the expert opinion, we do not think it necessary to go into the merits of the case in view of the course we propose to adopt, and in view of the fact that the Commission is the last fact finding authority in the scheme of the Act.

Tuesday, June 3, 2025

207 CrPC

P. Gopalkrishnan v. State of Kerala, (2020) 9 SCC 161 : 2019 SCC OnLine SC 1532 at page 182

18. Be that as it may, the Magistrate's duty under Section 207 at this stage is in the nature of administrative work, whereby he is required to ensure full compliance of the section. We may usefully advert to the dictum in Hardeep Singh v. State of Punjab [Hardeep Singh v. State of Punjab, (2014) 3 SCC 92 : (2014) 2 SCC (Cri) 86] wherein it was held that : (SCC p. 123, para 47)

"47. Since after the filing of the charge-sheet, the court reaches the stage of inquiry and as soon as the court frames the charges, the trial commences, and therefore, the power under Section 319(1) CrPC can be exercised at any time after the charge-sheet is filed and before the pronouncement of judgment, except during the stage of Sections 207/208 CrPC, committal, etc. which is only a pre-trial stage, intended to put the process into motion. This stage cannot be said to be a judicial step in the true sense for it only requires an application of mind rather than a judicial application of mind. At this pre-trial stage, the Magistrate is required to perform acts in the nature of administrative work rather than judicial such as ensuring compliance with Sections 207 and 208 CrPC, and committing the matter if it is exclusively triable by the Sessions Court."

Thursday, May 22, 2025

Accused has a right to watch witness

[Jayendra Vishnu Thakur v. State of Maharashtra, MANU/SC/0995/2009MANU/SC/0995/2009 : (2009) 7 SCC 104 : (2010) 2 SCC (Cri) 500] as quoted above, that the right of the accused to watch the prosecution witness is a valuable right, also need not detain us.

Mohammed Faruk vs. Union of India (21.03.2025 - MADHC) : MANU/TN/1086/2025

Appearance through Pleader permitted

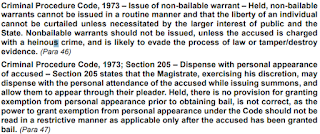

CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. OF 2024 (ARISING OUT OF SPECIAL LEAVE PETITION (CRL.) NO. 1074 OF 2017) SHARIF AHMED AND ANOTHER versus STATE OF UTTAR PRADESH AND ANOTHER Criminal Procedure Code, 1973; Section 173(2) – Contents of chargesheet – The need to provide lead details of the offence in the chargesheet is mandatory as it is in accord with paragraph 122 of the police regulations. The investigating officer must make clear and complete entries of all columns in the chargesheet so that the court can clearly understand which crime has been committed by which accused and what the material evidence available. Statements under Section 161 of the Code and related documents have to be enclosed with the list of witnesses. Substantiated reasons and grounds for an offence being made in the chargesheet are a key resource for a Magistrate to evaluate whether there are sufficient grounds for taking cognisance, initiating proceedings, and then issuing notice, framing charges etc. (Para 20, 31 & 31) Criminal Procedure Code, 1973; Section 173(8) – The requirement of "further evidence" or a "supplementary chargesheet" as referred to under Section 173(8) of the Code, is to make additions to a complete chargesheet, and not to make up or reparate for a chargesheet which does not fulfil requirements of Section 173(2) of the Code. (Para 13) Criminal Procedure Code, 1973; Section 204 – Issue of summons – Section 204 of the Code does not mandate the Magistrate to explicitly state the reasons for issue of summons and this is not a prerequisite for deciding the validity of the summons. Nevertheless, the summons should be issued when it appears to the Magistrate that there is sufficient ground for proceeding against the accused. The Magistrate in terms of Section 204 of the Code is required to exercise his judicial discretion with a degree of caution, even when he is not required to record reasons, on whether there is sufficient ground for proceeding. (Para 17) Criminal Procedure Code, 1973; Section 173(2), 190 & 204 – There is an inherent connect between the chargesheet submitted under Section 173(2) of the Code, cognisance which is taken under Section 190 of the Code, issue of process and summoning of the accused under Section 204 of the Code, and thereupon issue of notice under Section 251 of the Code, or the charge in terms of Chapter XVII of the Code. The details set out in the chargesheet have a substantial impact on the efficacy of procedure at the subsequent stages. The chargesheet is integral to the process of taking cognisance, the issue of notice and framing of charge, being the only investigative document and evidence available to the court till that stage. (Para 20) Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 – Object and purpose of police investigation – Includes the need to ensure transparent and free investigation to ascertain the facts, examine whether or not an offence is committed, identify the offender if an offence is committed, and to lay before the court the evidence which has been collected, the truth and correctness of which is thereupon decided by the court. (Para 26) 2 Indian Penal Code, 1860; Section 406 – Criminal breach of trust – Section 406 requires entrustment, which carries the implication that a person handing over any property or on whose behalf the property is handed over, continues to be the owner of the said property. Further, the person handing over the property must have confidence in the person taking the property to create a fiduciary relationship between them. A normal transaction of sale or exchange of money/consideration does not amount to entrustment. (Para 36) Indian Penal Code, 1860; Section 415 – Cheating – The offence of cheating requires dishonest inducement, delivering of a property as a result of the inducement, and damage or harm to the person so induced. The offence of cheating is established when the dishonest intention exists at the time when the contract or agreement is entered, for the essential ingredient of the offence of cheating consists of fraudulent or dishonest inducement of a person by deceiving him to deliver any property, to do or omit to do anything which he would not do or omit if he had not been deceived. (Para 37) Indian Penal Code, 1860; Section 506 – Criminal intimidation – An offence of criminal intimidation arises when the accused intendeds to cause alarm to the victim, though it does not matter whether the victim is alarmed or not. The word 'intimidate' means to make timid or fearful, especially: to compel or deter by or as if by threats. The threat communicated or uttered by the person named in the chargesheet as an accused, should be uttered and communicated by the said person to threaten the victim for the purpose of influencing her mind. The word 'threat' refers to the intent to inflict punishment, loss or pain on the other. Mere expression of any words without any intent to cause alarm would not be sufficient to bring home an offence under Section 506 of the IPC. (Para 38) Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 – Issue of non-bailable warrant – Held, non-bailable warrants cannot be issued in a routine manner and that the liberty of an individual cannot be curtailed unless necessitated by the larger interest of public and the State. Nonbailable warrants should not be issued, unless the accused is charged with a heinous crime, and is likely to evade the process of law or tamper/destroy evidence. (Para 46) Criminal Procedure Code, 1973; Section 205 – Dispense with personal appearance of accused – Section 205 states that the Magistrate, exercising his discretion, may dispense with the personal attendance of the accused while issuing summons, and allow them to appear through their pleader. Held, there is no provision for granting exemption from personal appearance prior to obtaining bail, is not correct, as the power to grant exemption from personal appearance under the Code should not be read in a restrictive manner as applicable only after the accused has been granted bail. (Para 47)

ex parte disposal of criminal appeals

141. In the case reported in (K. Muruganandam v. State Represented by the Deputy Superintendent of Police)5, while emphasizing the need that a criminal appeal should not be dismissed for non-prosecution, it was held in para-6 as under:

"6. It is well settled that if the accused does not appear through counsel appointed by him/her, the Court is obliged to proceed with the hearing of the case only after appointing an Amicus Curiae, but cannot dismiss the appeal merely because of non-representation or default of the advocate for the accused (see Kabira v. State of U.P. [Kabira v. State of U.P., 1981 Supp SCC 76] and Mohd. Sukur Ali v. State of Assam [Mohd. Sukur Ali v. State of Assam, (2011) 4 SCC 729])."

Monday, May 5, 2025

if not arrested during investigation - no need for arrest later on

The Hon'ble Supreme Court in Siddharth v. State of U.P., (2022) 1 SCC 676 while expounding on the issue of accused's cooperation with the investigation and curtailment of personal liberty was pleased to observe that:

9. We are in agreement with the aforesaid view of the High Courts and would like to give our imprimatur to the said judicial view. It has rightly been observed on consideration of Section 170 CrPC that it does not impose an obligation on the officer-in-charge to arrest each and every accused at the time of filing of the charge-sheet. We have, in fact, come across cases where the accused has cooperated with the investigation throughout and yet on the charge-sheet being filed non-bailable warrants have been issued for his production premised on the requirement that there is an obligation to arrest the accused and produce him before the court. We are of the view that if the investigating officer does not believe that the accused will abscond or disobey summons he/she is not required to be produced in custody. The word "custody" appearing in Section 170 CrPC does not contemplate either police or judicial custody but it merely connotes the presentation of the accused by the investigating officer before the court while filing the charge-sheet.

10. We may note that personal liberty is an important aspect of our constitutional mandate. The occasion to arrest an accused during investigation arises when custodial investigation becomes necessary or it is a heinous crime or where there is a possibility of influencing the witnesses or accused may abscond. Merely because an arrest can be made because it is lawful does not mandate that arrest must be made. A distinction must be made between the existence of the power to arrest and the justification for exercise of it [Joginder Kumar v. State of U.P., (1994) 4 SCC 260 : 1994 SCC (Cri) 1172] . If arrest is made routine, it can cause incalculable harm to the reputation and self-esteem of a person. If the investigating officer has no reason to believe that the accused will abscond or disobey summons and has, in fact, throughout cooperated with the investigation we fail to appreciate why there should be a compulsion on the officer to arrest the accused.

Tuesday, April 8, 2025

Thursday, January 30, 2025

Forgery - Fraud on court and 340 or contempt

Re: whether presenting a false document amounts to Fraud on court and same should be decided at threshold or preliminary stage ?

| Case Title | Issue | Relevant Observations |

| Ramrameshwari Devi v. Nirmala Devi, (2011) 8 SCC 249 | Although there are complex facts involved in the case and issues does not pertain to our research. However, the SC made same significant observation. The brief case pertains to wherein the appellant was claiming certain reliefs in respect of suit property. The Court Highlighted the issue of frivolous, and uncalled litigation wherein parties deliberately institute the case to frustrate and create obstacles to prolong the course of proceedings of lower courts. | Relevant portion is Highlighted The main question which arises for our consideration is whether the prevailing delay in civil litigation can be curbed? In our considered opinion the existing system can be drastically changed or improved if the following steps are taken by the trial courts while dealing with the civil trials: A. Pleadings are the foundation of the claims of parties. Civil litigation is largely based on documents. It is the bounden duty and obligation of the trial Judge to carefully scrutinise, check and verify the pleadings and the documents filed by the parties. This must be done immediately after civil suits are filed. B. The court should resort to discovery and production of documents and interrogatories at the earliest according to the object of the Act. If this exercise is carefully carried out, it would focus the controversies involved in the case and help the court in arriving at the truth of the matter and doing substantial justice. C. Imposition of actual, realistic or proper costs and/or ordering prosecution would go a long way in controlling the tendency of introducing false pleadings and forged and fabricated documents by the litigants. Imposition of heavy costs would also control unnecessary adjournments by the parties. In appropriate cases the courts may consider ordering prosecution otherwise it may not be possible to maintain purity and sanctity of judicial proceedings. D. The court must adopt realistic and pragmatic approach in granting mesne profits. The court must carefully keep in view the ground realities while granting mesne profits. E. The courts should be extremely careful and cautious in granting ex parte ad interim injunctions or stay orders. Ordinarily short notice should be issued to the defendants or respondents and only after hearing the parties concerned appropriate orders should be passed. |

| Chandra Shashi v. Anil Kumar Verma, (1995) 1 SCC 421 | The issue addressed in this was whether the filing of forged or fabricated document in the court of laws amounts to interference in the administration of Justice and thus punishable by Criminal contempt of Court. The brief case was the Respondent husband presented a false and fabricated document to oppose the prayer of wife seeking the transfer of matrimonial proceedings. On finding the documents to be forged the SC initiated Suo moto Contempt case. | Relevant Observations Para 14 14. The legal position thus is that if the publication be with intent to deceive the court or one made with an intention to defraud, the same would be contempt, as it would interfere with administration of justice. It would, in any case, tend to interfere with the same. This would definitely be so if a fabricated document is filed with the aforesaid mens rea. In the case at hand the fabricated document was apparently to deceive the court; the intention to defraud is writ large. Anil Kumar is, therefore, guilty of contempt. |

| Meghmala v. G. Narasimha Reddy, (2010) 8 SCC 383 | The controversy in the case is not related to our research but the court the SC made some crucial observations regarding Fraud and suppression of material facts. The Brief facts was that there was land grabbing dispute under A.P. Land Grabbing Act b/w appellant -Respondent. Though there are several issues involved, one of the issues were the non-disclosure or suppression sale deed while obtaining court order. The court explained the Fraud on Court by Non-disclosure of facts necessary for adjudication and its effects | Relevant Observations Para 32, 33, 34, 36 36. From the above, it is evident that even in judicial proceedings, once a fraud is proved, all advantages gained by playing fraud can be taken away. In such an eventuality the questions of non-executing of the statutory remedies or statutory bars like doctrine of res judicata are not attracted. Suppression of any material fact/document amounts to a fraud on the court. Every court has an inherent power to recall its own order obtained by fraud as the order so obtained is non est. 34. An act of fraud on court is always viewed seriously. A collusion or conspiracy with a view to deprive the rights of the others in relation to a property would render the transaction void ab initio. Fraud and deception are synonymous. Although in a given case a deception may not amount to fraud, fraud is anathema to all equitable principles and any affair tainted with fraud cannot be perpetuated or saved by the application of any equitable doctrine including res judicata. Fraud is proved when it is shown that a false representation has been made (i) knowingly, or (ii) without belief in its truth, or (iii) recklessly, careless whether it be true or false. Suppression of a material document would also amount to a fraud on the court. (Vide S.P. Chengalvaraya Naidu [(1994) 1 SCC 1 : AIR 1994 SC 853] , Gowrishankar v. Joshi Amba Shankar Family Trust [(1996) 3 SCC 310 : AIR 1996 SC 2202] , Ram Chandra Singh v. Savitri Devi [(2003) 8 SCC 319] , Roshan Deen v. Preeti Lal [(2002) 1 SCC 100 : 2002 SCC (L&S) 97 : AIR 2002 SC 33] , Ram Preeti Yadav v. U.P. Board of High School & Intermediate Education [(2003) 8 SCC 311 : AIR 2003 SC 4268] and Ashok Leyland Ltd. v. State of T.N. [(2004) 3 SCC 1 : AIR 2004 SC 2836] ) 32. The ratio laid down by this Court in various cases is that dishonesty should not be permitted to bear the fruit and benefit to the persons who played fraud or made misrepresentation and in such circumstances the Court should not perpetuate the fraud. (See Vizianagaram Social Welfare Residential School Society v. M. Tripura Sundari Devi [(1990) 3 SCC 655 : 1990 SCC (L&S) 520 : (1990) 14 ATC 766] , Union of India v. M. Bhaskaran [1995 Supp (4) SCC 100 : 1996 SCC (L&S) 162 : (1996) 32 ATC 94] , Kendriya Vidyalaya Sangathan v. Girdharilal Yadav [(2004) 6 SCC 325 : 2005 SCC (L&S) 785] , State of Maharashtra v. Ravi Prakash Babulalsing Parmar [(2007) 1 SCC 80 : (2007) 1 SCC (L&S) 5] , Himadri Chemicals Industries Ltd. v. Coal Tar Refining Co. [(2007) 8 SCC 110 : AIR 2007 SC 2798] and Mohd. Ibrahim v. State of Bihar [(2009) 8 SCC 751 : (2009) 3 SCC (Cri) 929] .) 33. Fraud is an intrinsic, collateral act, and fraud of an egregious nature would vitiate the most solemn proceedings of courts of justice. Fraud is an act of deliberate deception with a design to secure something, which is otherwise not due. The expression "fraud" involves two elements, deceit and injury to the person deceived. It is a cheating intended to get an advantage. [Vide Vimla (Dr.) v. Delhi Admn. [AIR 1963 SC 1572 : (1963) 2 Cri LJ 434] , Indian Bank v. Satyam Fibres (India) (P) Ltd. [(1996) 5 SCC 550] , State of A.P. v. T. Suryachandra Rao [(2005) 6 SCC 149 : AIR 2005 SC 3110] , K.D. Sharma v. SAIL [(2008) 12 SCC 481] and Central Bank of India v. Madhulika Guruprasad Dahir [(2008) 13 SCC 170 : (2009) 1 SCC (L&S) 272] .] |

| S.P. Chengalvaraya Naidu v. Jagannath, (1994) 1 SCC 1 | The issue involved in this case was obtaining of decree on the basis of non-disclosure of material and relevant facts werein the Appellant prayed for partition without disclosing that the deed of release relinquishing his right in respect of said suit property. The court traced the meaning of Fraud | 5. The High Court, in our view, fell into patent error. The short question before the High Court was whether in the facts and circumstances of this case, Jagannath obtained the preliminary decree by playing fraud on the court. The High Court, however, went haywire and made observations which are wholly perverse. We do not agree with the High Court that "there is no legal duty cast upon the plaintiff to come to court with a true case and prove it by true evidence". The principle of "finality of litigation" cannot be pressed to the extent of such an absurdity that it becomes an engine of fraud in the hands of dishonest litigants. The courts of law are meant for imparting justice between the parties. One who comes to the court, must come with clean hands. We are constrained to say that more often than not, process of the court is being abused. Property-grabbers, tax-evaders, bank-loan-dodgers and other unscrupulous persons from all walks of life find the court-process a convenient lever to retain the illegal gains indefinitely. We have no hesitation to say that a person, who's case is based on falsehood, has no right to approach the court. He can be summarily thrown out at any stage of the litigation. |

| | | |

Thursday, January 23, 2025

Burden of Proof

Re: Burden of Proof and Onus of Proof

| Case Title | Issue | Relevant Observations |

| Phoenix Mills Ltd. v. Union of India, 2004 SCC OnLine Bom 33 | | Read Para 17 ……..The burden always lies on the person who asserts that the particular goods are excisable. It lies at first on the party who would be unsuccessful if no evidence at all was given on either side. There is essential distinction between burden of proof and onus of proof. The burden of proof lies upon the person who has to prove a fact and it never shifts, but the onus of proof shifts. Onus means the duty of adducing evidence. Assuming that onus has shifted on the petitioner, then, the evidence produced by the petitioners has substantially established the link between the material supplied and used by the petitioners. |

| Narayan Govind Gavate v. State of Maharashtra, (1977) 1 SCC 133 | | Read para 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 19. "Proof", which is the effect of evidence led, is defined by the provisions of Section 3 of the Evidence Act. The effect of evidence has to be distinguished from the duty or burden of showing to the court what conclusions it should reach. This duty is called the "onus probandi", which is placed upon one of the parties, in accordance with appropriate provisions of law applicable to various situations; but, the effect of the evidence led is a matter of inference or a conclusion to be arrived at by the Court. 20. The total effect of evidence is determined at the end of a proceeding not merely by considering the general duties imposed by Sections 101 and 102 of the Evidence Act but also the special or particular ones imposed by other provisions such as Sections 103 and 106 of the Evidence Act. Section 103 enacts: "103. The burden of proof as to any particular fact lies on that person who wishes the Court to believe in its existence, unless it is provided by any law that the proof of that fact shall lie on any particular person." And, Section 106 lays down: "106. When any fact is especially within the knowledge of any person, the burden of proving that fact is upon him." 21. In judging whether a general or a particular or special onus has been discharged, the court will not only consider the direct effect of the oral and documentary evidence led but also what may be indirectly inferred because certain facts have been proved or not proved though easily capable of proof if they existed at all which raise either a presumption of law or of fact. Section 114 of the Evidence Act covers a wide range of presumptions of fact which can be used by courts in the course of administration of justice to remove lacunae in the chain of direct evidence before it. It is, therefore, said that the function of a presumption often is to "fill a gap" in evidence. 22. True presumptions, whether of law or of fact, are always rebuttable. In other words, the party against which a presumption may operate can and must lead evidence to show why the presumption should not be given effect to. If, for example, the party which initiates a proceeding or comes with a case to court offers no evidence to support it, the presumption is that such evidence does not exist. And, if some evidence is shown to exist on a question in issue, but the party which has it within its power to produce it, does not, despite notice to it to do so, produce it, the natural presumption is that it would, if produced, have gone against it. Similarly, a presumption arises from failure to discharge a special or particular onus. 23. The result of a trial or proceeding is determined by a weighing of the totality of facts and circumstances and presumptions operating in favour of one party as against those which may tilt the balance in favour of another. Such weighment always takes place at the end of a trial or proceeding which cannot, for purposes of this final weighment, be split up into disjointed and disconnected parts simply because the requirements of procedural regularity and logic, embodied in procedural law, prescribe a sequence, a stage, and a mode of proof for each party tendering its evidence. What is weighed at the end is one totality against another and not selected bits or scraps of evidence against each other. |

| Babu v. State of Kerala, (2010) 9 SCC 189 | | 27. Every accused is presumed to be innocent unless the guilt is proved. The presumption of innocence is a human right. However, subject to the statutory exceptions, the said principle forms the basis of criminal jurisprudence. For this purpose, the nature of the offence, its seriousness and gravity thereof has to be taken into consideration. The courts must be on guard to see that merely on the application of the presumption, the same may not lead to any injustice or mistaken conviction. Statutes like the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881; the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988; and the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act, 1987, provide for presumption of guilt if the circumstances provided in those statutes are found to be fulfilled and shift the burden of proof of innocence on the accused. However, such a presumption can also be raised only when certain foundational facts are established by the prosecution. There may be difficulty in proving a negative fact. 28. However, in cases where the statute does not provide for the burden of proof on the accused, it always lies on the prosecution. It is only in exceptional circumstances, such as those of statutes as referred to hereinabove, that the burden of proof is on the accused. The statutory provision even for a presumption of guilt of the accused under a particular statute must meet the tests of reasonableness and liberty enshrined in Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution |

| Ishar Das v. Administrator, Union Territory of Delhi, 1975 SCC OnLine Del 60 | . | 15. Subba Rao, J. (as he then was), speaking for the Supreme Court in Raghavamma v. A. Chenchamma (A.I.R. 1964 S.C. 136 at p. 143) (7) referring to sections 101 to 103 explained the distinction between burden of proof and onus of proof in the following terms: "There is an essential distinction between Burden of proof and onus of proof: burden of proof lies upon the person who has to prove a fact and it never shifts, but the onus of proof shifts. The burden of proof in the present case undoubtedly lies upon the plaintiff to establish the factum of adoption and that of partition. The said circumstances do not alter the incidence of the burden of proof. Such considerations, having regard to the circumstances of a particular case, may shift the onus of proof. Such a shifting of onus is a continuous process in the evaluation of evidence. 16. The burden of proof that lies under Section 101 and that under Section 102 of the Evidence Act is distinguishable: the former has been described as a "legal" or "persuasive burden" and the latter as the evidential burden or as the "burden of adducing evidence" (Phipson). It is easy enough to say concerning the legal or persuasive burden that it lies on whichever party would fail if no evidence were given on either side or if the allegation to be proved is struck out of the record. But, as Rupert Cross points out "A moment's reflection should suffice to show that these tests are only applicable to the evidential burden; they cannot apply to the legal burden in all cases." "As a matter of commonsense", "the legal burden of proving all facts essential to their claims normally rests upon the plaintiff in a civil suit or that prosecutor in criminal proceedings"; it would go to such length as the burden of proof of the assertion still resting upon the plaintiff even "if the assertion of a negative is an essential part of the plaintiff's case." (Vide Bowen, L.J. in Abrath v. North Eastern Rail, Co., 1883 11 Q.B.D. 440 at p. (457) (8) a decision which was affirmed by the House of Lords in (1886) 11 A.C. 247). Cross explains the difficulty which may sometimes arise with regard to the question whether an assertion is essential to a party's case or that of the adversary by referring to the decision of the House of Lords in Joseph Constantine Steamship Line, Ltd. v. Imperial Smelting Corporation, Ltd. (1942 A.C. 154) (9). In that case the charterer of the ship claimed damages from the owners for failure to load; the owners pleaded frustration of the contract by reason of the destruction of the ship owing to an explosion. The question of fact for determination was whether the explosion had been caused by the fault of the owner, but the evidence was scanty on this question. The House of Lords held that the plaintiff had the legal burden of proving default when frustration of the contract was pleaded. In some cases, as Cross explains, it becomes necessary to ascertain the "legal burden of proof" even after consulting the precedents concerned with the various branches of substantive law. Even greater difficulty arises when the existence or non-existence of any fact in issue may be known for certain by one of the parties and this is often said to have an important bearing on the incident of burden of proof of that fact. Reference in this connection is made by him to R. v. Turner, (1816) 5 m. & S. 206) where the accused was prosecuted for having pheasants and hares in his possession without the necessary qualification or authorisation; ten possible qualifications had been mentioned in the relevant statute. The King's Bench held that it was unnecessary for the Crown to prove that these qualifications did not apply to the case. In R. v. Spurge, (1961) 2 Q.B. 205 it was held that "there was no rule of law that where the facts are peculiarly within the knowledge of the accused the burden of establishing any defence based on these facts shifts to the accused" 18. Reference has been made to some of these aspects in an endeavour to comprehend the amplitude of the concept of the "shifting" of onus as a "continuous process in the evaluation of evidence" as explained by Subba Rao J. The above passages from Cross and the legal literature on the subject cited by him clearly show that in some cases at least it may not be enough to start at the point where the onus shifts from the landlord to the tenant and to let it stay with him for ever, unless by what he has done or failed to show, in other words, by his failure to play the ball back to the other, the legal burden which has been placed on the landlord, under this piece of substantive law has been discharged. It cannot, for instance, be said that once the landlord gives a version of the tenant's means, however fanciful it may be the onus shifts to the tenant, it stays permanently with him thereafter and that the landlord has nothing further to do with it. To say so would obviously be to throw the burden on the tenant despite Section 19 laying the legal burden, in terms of section 101 of the Evidence Act, on the landlord. It is, therefore, crucial to understand the distinction what Subba Rao, J. explained as the distinction between "burden of proof" and "onus of proof and the "onus of proof" being "continuously shifting in the appreciation of evidence". It would be an easy enough situation where the tenant does not let in any evidence at all or is seen to be guilty of fraudulent conduct and suppresses such evidence as may be in his possession or power and such suppression may in the circumstances of the case give rise to an adverse inference being properly drawn against him. The difficulty in appreciating the evidence in a situation of "shifting of onus as a continuous process", cannot be overcome by reliance on crutches like "unclean hands", an expression |

Monday, January 13, 2025

Limitation to challenge Award S. 34 Arbitration

Limitation for filing S. 17 application under Arbitration Act, 1940 begins from awareness of award's availability, not receipt of copy

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)